Epileptic Disorders

MENURoom tilt illusion in epilepsy Volume 23, issue 6, December 2021

Room tilt illusion (RTI) is a rare phenomenon in which a person transiently perceives their surroundings as tilted sideways or upside-down. It was first reported in 1805 when Bishopp described a 22-year-old woman who saw attendants stand on their heads, which she found amusing; her symptoms lasted for one hour and resolved with “ordinary treatment of hysteria” [1, 2]. RTI is typically around the center of vision and involves the entire surroundings and can be clockwise or counterclockwise [2, 3]. The deviation is typically in the frontal plane, at 90̊ or 180̊, although tilts of 30̊, 45̊, 150̊, 160̊ or other angles have also been reported [2, 4], as have those that occur in the anterior-posterior (coronal) plane [3, 5]. Patients usually have no altered or tilted perception of their own vertical orientation (normal egocentric perception) [3, 6]. Patients can have accompanying nausea or dizziness [3, 7]. RTI starts suddenly, lasts a few seconds to hours, rarely a day or more, and resolves suddenly or slowly [2]. For reviews of the literature, see Sierra-Hidalgo et al. [2] and Solms et al. [3].

RTI is caused by many conditions including stroke and migraine, and has also been described in epileptic patients, although to date, there has been no documented case using EEG. Here, we report a case of RTI that is documented by video-EEG monitoring to be epileptic in nature. This is important because it expands our understanding of how epilepsy can present.

Case study

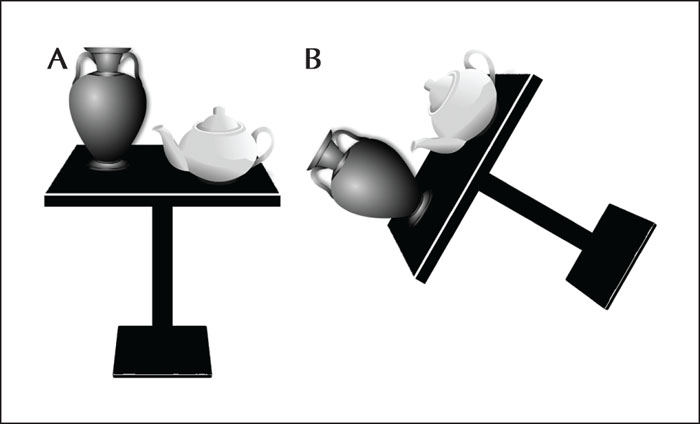

Our patient is a 30-year-old woman with an 11-year history of stereotypical spells involving sudden perception that objects in front of her are tilted counterclockwise. The perceived tilt is about 60̊, e.g., a table in front of her appears tilted on its side (figure 1). The episodes last for 1-2 seconds and are associated with a momentary “head sensation” and “weird zap sensation behind the eyes”, and if standing, she briefly feels unsteady but not tilted. There is no vertigo, nausea, tinnitus, hearing loss, aural fullness, or other neurological symptoms. The episodes occur approximately two times per month and are independent of head/body position. Interictally, she is “totally fine.” She has no history of trauma, meningitis, encephalitis, or febrile seizures, and her family history includes a sister with “myoclonic” seizures. Her initial EEG performed locally, approximately a decade prior to presentation, showed “occasional bursts of generalized irregular spike slow-wave activity lasting 2-3 seconds”. Overall, the impression of her neurologist at the time was that her spells were psychogenic.

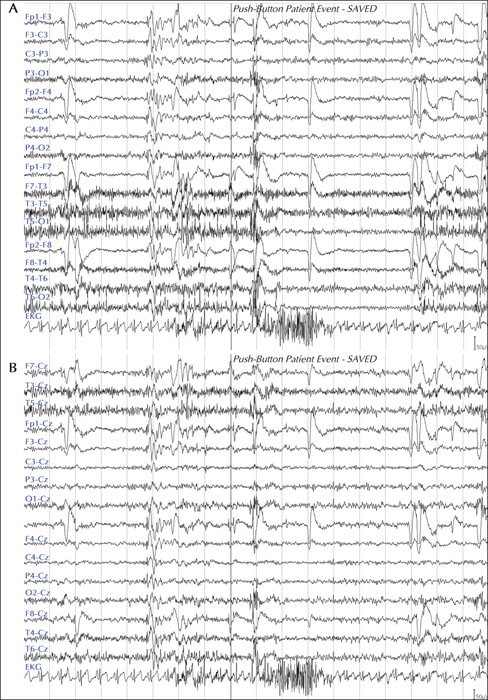

The patient presented to our university for evaluation of her spells. Her interictal neurological examination was normal, without nystagmus. Her brain MRI demonstrated a left frontoparietal venous angioma. Neuropsychological testing was normal. During two days of video-EEG monitoring, she had three of her typical spells. The video did not show any obvious clinical correlates, such as unsteadiness or body tilt. The EEG showed a reproducible brief generalized spike-wave burst that coincided temporally with her symptoms in all the spells and with her pushing the button to alert the nurses. There were no asymmetric hemispheric spike discharges (figure 2). Her interictal EEG revealed normal background activity for awake and sleep states, no epileptiform discharges, and no slow waves.

She was diagnosed with epilepsy and was started on topiramate, which resolved her symptoms. At a six-month follow-up visit, she was still symptom-free.

Discussion

Here, we report the first case of RTI associated with epilepsy. Although rare, RTI is possibly under-reported, in part, because patients may fear being labeled as psychogenic [5].

RTI is theorized to be due to a transient mismatch, at the cortical level, of 3-dimensional integration of the perceived vertical between vestibular-visual-proprioceptive inputs [2, 7]. Since it is typically brief, it is hypothesized that the cortex dynamically and quickly corrects the mismatch to avoid the perception of two verticals [2, 7]. The cause for such mismatch is believed to be disruption in the sensory system, most commonly associated with vestibular disorders. This is because vestibular structures are frequently disrupted in RTI, as seen in posterior circulation strokes which are a common cause of RTI [2, 4]. In addition, RTI is also seen in peripheral vestibulopathies such as Meniere [2, 5]. Further, most RTI patients have associated vestibular symptoms [7]. Also, RTI is reported in patients with migraine, in which vestibular structures are implicated [8]. Moreover, RTI is reported in subjects who experience microgravity, and astronauts have occasional inversion illusion [7]. Finally, RTI was induced by otolith stimulation via off vertical axis rotation (OVAR) in three patients with brainstem lesions and skew deviation [9]. In addition to examples of acute vestibular dysfunction, RTI is also seen in cases of acute disruption in proprioceptive sensory inputs, such as in Guillain Barre syndrome and spinal cord injuries [2]. We have also observed a patient with Chiari I malformation who has discreet episodes of RTI lasting for a few minutes, in which the room suddenly flips upside down. Therefore, RTI is associated with conditions in which peripheral or central vestibular (or less commonly proprioceptive) structures are involved.

Despite the known involvement of the vestibular and proprioceptive systems, RTI remains incompletely understood. This is because RTI is reported not only in patients with acute focal vestibular or proprioceptive sensory lesions, but also in those with chronic or diffuse central nervous system disorders, and conditions that cannot be causally linked to a known sensory dysfunction [2]. For example, RTI is seen in patients with brain abscesses or tumors in all cortical lobes including the frontal and parietal lobes [2, 3, 7], and in those with multiple sclerosis or multiple system atrophy [2]. Furthermore, even though the vestibular nuclei seem critically involved in RTI [4, 7], cases involving the cerebellum, thalamus, all cortical lobes, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system have all been implicated [2, 9], making anatomical location of RTI difficult.

RTI is different from other vestibular phenomena, such as subjective visual vertical (SVV). SVV is seen when a patient aligns an object, such as a rod, a few degrees off vertical. The patient is unaware of this abnormality and there is no perception that the world is tilted; the degree of tilt in SVV is almost always small, less than 10-20̊. SVV lasts days to weeks and is common, occurring in most patients with posterior fossa strokes- for a recent review of SVV in stroke, see Shaban et al. [10]. Finally, one patient with RTI was tested for SVV which was shown to be negative, indicating that the two phenomena are distinct [9].

Similarly, RTI is different from ocular tilt reaction (OTR), which includes a triad of head tilt, skewed deviation, and ocular cyclorotation. OTR is seen in brainstem lesions but not in cortical, spinal cord, or neuropathy conditions [11]. In addition, OTR is not associated with a perceived tilt of the environment and its cyclorotation is less than 15̊; therefore, it cannot account for RTI [4].

Epilepsy is reported as a probable cause of RTI in many studies. Smith described the vestibular symptoms of 120 patients as a component of their epilepsy. He reported that some described themselves or their environment as being tilted, but no EEG result was reported [12]. Ropper described a case of RTI in one quadrant of vision, instead of the entire visual field, with the patient displaying a normal EEG during the episode [4]. Gondim et al. reported a patient with a prior pontine infarct who had one-hour RTI spells consisting of 180̊ inversion; although the video-EEG was normal during the spells, the spells resolved with gabapentin [13].

The cause of epilepsy in our patient is presumably a form of idiopathic generalized epilepsy given previous interictal epileptiform discharges and her present reproducible ictal generalized epileptiform discharges. However, a frontal lobe seizure focus with secondary bilateral synchrony is also a possible cause, and, considering her ictal semiology (preserved consciousness with awareness of her vestibular symptomatology), is perhaps more likely [3, 7, 12]. As noted, RTI has been reported in all cortical lobes including frontal and parietal cortices, and our patient has a left frontoparietal venous angioma. However, venous angiomas are rare in epileptic patients and the causal relationship between venous angiomas and seizures remains possible [14], but uncertain [15]. Therefore, since RTI has been reported in patients with focal lesions in all brain lobes, it is conceivable that our patient's epilepsy, rather than being truly idiopathic generalized epilepsy, is focal with secondary bilateral synchrony, and is due to her frontoparietal venous angioma.

In conclusion, we report a case of RTI associated with epilepsy, which is, to our knowledge, the first report implicating epilepsy as a cause of RTI. Therefore, this report adds to our understanding of vestibular manifestations in patients with epilepsy which may improve diagnosis, workup, and treatment of patients with RTI.

Supplementary material

Summary slides accompanying the manuscript are available at www.epilepticdisorders.com.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors acknowledge the support of Drs Hal Adams, James Corbett, and Thomas Brandt.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Senior author DF checked with the institutional IRB and, since this is a case report of one patient, no IRB was needed.