Epileptic Disorders

MENUIs it juvenile myoclonic epilepsy? Volume 2, issue 1, Mars 2000

Case report

This man was born at term to healthy, non-consanguineous parents with no family history of epilepsy or other neurological disorders. The pregnancy was induced by hormonal treatment and was marked by recurrent vomiting and a nephretic colic. He is the first of three children, his younger sister and brother are in good health. Neonatal distress was reported. The APGAR score was 5 at 1 minute. His birth weight was 3,500 grams. Mental, language, motor and physical development were markedly delayed; walking was achieved at 30 months.

During the subsequent stages of development, there were no episode of worsening or slowing, and the encephalopathy was considered fixed and non-progressive. His schooling was limited. He works presently in a specialized center for mentally handicaped persons. Puberty appeared around age 16.

At age 19 years, spontaneous MJ of the arms were observed, especially on waking in the morning. One year later, two months after the beginning of treatment with sulpiride for behavioral problems, sudden falls without loss of consciousness, preceded by MJ of the upper limbs, occurred. All seizure were spontaneous and occurred especially, but not exclusively after waking in the morning. At age 21 years, he was referred to us after a first GTCS which had been preceded by a cluster of MJ.

Physical examination revealed a small stature, with a height of 143 cm and a weight of 39.5 kg. Head circumference was 53 cm. There was enlargement of the thorax and he had had surgery for scoliosis. Neurological examination revealed hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, bilateral Babinski sign, severe mental retardation, retinis pigmentosa, and external strabismus of the left eye. Etiological factors of this encephalopathy were not found. Muscle biopsy was nonspecifc without ragged red fibers or changes evocative of mitochondrial disorders. Skin biopsy and karyotype were normal. Metabolic screening included amino acids, very long chain fatty acids, serum lactate and pyruvate determination. Hormone assay included FSH, LH, ACTH, cortisol, TSH, FT3, FT4, testosterone. All the results were normal, except for the detection of subclinical minor thalassemia.

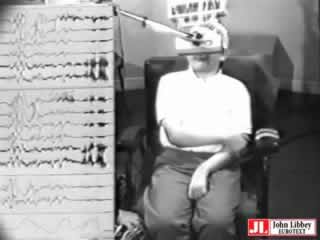

Waking interictal EEG showed normal background activity and generalized SW and PSW discharges. Some were clearly asymmetrical, changing from one hemisphere to the other during the same recording (figure 1). Photic stimulation disclosed a photoparoxysmal response, sometimes associated with MJ (figure 1 and video). Three spontaneous jerks accompanied by a burst of generalized PSW were recorded on awakening from a nap (figure 2).

MRI disclosed wide ventricles, a thin corpus callosum, brainstem atrophy, and so-called "redundant gyration", with an important loss of white matter (figures 3 and 4). These lesions were considered to be markers of acquired pre- or perinatal brain damage that could have occurred late during pregnancy. The rest of the T2-weighted examination disclosed the presence of a periventricular high signal in the white matter, consistent with sequellae of periventricular leucomalacia.

In spite of the general neurological background, and due to the association of very evocative ictal symptomatology and interictal as well as ictal EEG recording, we diagnosed JME. Valproate was started as monotherapy, at 500 mg/d, then increased to 1,000 mg/d (plasma level: 82 mg/l) because of the occurrence of another GTCS, with complete control of seizures thereafter. During a 5-year follow-up, the routine waking EEG have remained consistently normal and the patient has remained seizure-free on VPA monotherapy, in spite of continuous, associated neuroleptic treatment (sulpiride was replaced over the years by levopromazine and propeciazine).

The International League Against Epilepsy [1] gives the following definition of JME: "JME appears around puberty and is characterized by seizures with bilateral, single or repetitive arrhythmic, irregular, MJ, predominantly in the arms. Jerks may cause some patients to fall suddenly. No disturbance of consciousness is noticeable. The disorder may be inherited. Often there are GTCS and, less often, infrequent absences. The seizures usually occur after awakening and are often precipitated by sleep deprivation. Interictal and ictal EEG have rapid, generalized, often irregular PSW. Frequently, the patients are photosensitive. Response to appropriate drugs is good."

Despite the presence of morphological brain abnormalities as shown by the MRI, severe mental retardation and diffuse neurological symptoms, this subject had a typical form of JME. Spontaneous MJ occurred at age 19, in the context of slightly delayed pubertal development. At age 21, he had a first GTCS that had been clearly introduced by a volley of MJ. There were no absences and no other seizure types. A history of MJ preceding a first GTCS (which constituted the motive for the first neurological consultation) is common in JME [2-4]. The EEG disclosed a normal background activity and typical fast generalized SW and PSW discharges. Asymmetrical changes without clear, constant focalization have been reported in JME [4, 7, 8]. The ictal changes we recorded were typical of JME, with the association of bilateral MJ with generalized fast PSW discharges. Monotherapy with VPA is reported to result in full seizure control in up to 85% of JME patients [3, 4, 9]. In this case, VPA achieved a complete control of MJ and GTCS over a follow-up of 5 years. The background activity remained consistently normal. The absence of progression of this condition was confirmed. Furthermore, MRI was consistent with sequellae of acquired perinatal damage. It disclosed abnormalities, all consistent with defective development of the white matter: large ventricles and subarachnoid spaces, atrophy of the corpus callosum and brainstem, so-called "redundant" gyration, periventricular gliosis, pointing to sequellae of an acquired anoxo/ischemic perinatal damage.

The association of mental retardation, epilepsy, slight build, photosensitivity and retinitis pigmentosa are evocative of a metabolic condition of the progressive myoclonus epilepsy (PME) type, especially of myoclonic encephalomyopathy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF) [10]. The age of onset varies between 3 and 65 years. Different clinical expressions of this type of epilepsy occur. Myoclonus with GTCS in a child or a young adult is the most typical feature. Partial seizures and drop attacks may sometimes be observed. The other features of the disease are deafness, in 50% of the cases, cerebellar ataxia, dementia, myopathy that is usually not obvious, lactic acidosis, optic atrophy, nanism, spasticity, sensory disorders, neuropathy, lipomas. On the EEG, anomalies of background activity are seen in 80% of cases [11, 12]. The other abnormalities include generalized SW and PSW discharges in 73%, diffuse slow delta bursts in 33%, focal anomalies in 40% and photosensitivity in 26%. Neuroradiological procedures do not display any specific lesion [10]. The differential diagnoses also includes Unverricht-Lundborg disease, ceroid-lipofuscinoses, and Lafora disease, among others, and even rarer forms of PME. In the present case however, the condition was clearly non-progressive, clinical history and all investigations allowed us to eliminate any metabolic disease and pointed to the existence of a fixed form of perinatally acquired encephalopathy.

Clinical experience shows that benign epilepsies can be diagnosed in neurologically abnormal patients. Benign myoclonic epilepsy of infancy has been reported in a patient with Down's syndrome (DS) [13]. Recently, Genton and Paglia (1994) [14] and Li et al. (1995) [15] reported the case of an elderly DS patient who had violent jerks on awakening, with falls and who later had GTCS. However, this late-onset, "senile" myoclonic epilepsy occurred in the context of progressive dementia. Even benign childhood epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes can occur in patients with brain lesions (review in [16]) e.g. in association with polymicrogyria [17].

In JME, abnormal (or "borderline") skull radiographs were initially reported by Janz and Christian (1957) [2]. They found a sclerosis of the crown, an overall thickening and a hyperostosis of the tabula interna with increased prevalence compared to normal and to other patients with epilepsy. Modern neuroimaging techniques including CT scan [18] or MRI have repeatedly failed to show abnormal findings. Serratosa and Delgado-Escueta (1993) detected no abnormalities in 60 MRI scans [19]. However, Woermann et al. (1999) [20] using the automated, objective technique of statistical parametric mapping for the analysis of structural MRI, recently found evidence of a mesiofrontal increase of grey matter in patients with JME. Cortical microdysgenesias have been reported in patients with various forms of IGE, especially with JME [21, 22]. These abnormalities are not seen in conventional neuroimaging procedures. Koepp et al. (1997) [23] reported increased flumazenil binding on PET scans in the thalamus, cerebellum and in the cerebral neocortex of patients with JME, which might be correlated with the presence of microdysgenesias. However, it had been reported earlier that 18-F2 deoxyglucose PET scans failed to show increased uptake in the frontal regions [24].

It may well be that clinicians refrain from diagnosing JME in patients who have significant brain pathology, and fail to include such patients in the series reported in the literature. In our experience, the diagnosis of JME may stand in the presence of abnormal neurological backgrounds. In our recent series of 170 JME cases, there was only 1 patient with severe neurological deficit (this case), but there was a much higher prevalence of psychiatric problems, including a significant personality disorder in 14% of the cases [25]. However, the nature of the association between JME and the neurological impairment remains unclear: is it purely fortuitous, or does the presence of neurological abnormalities influence the occurrence of the clinical symptoms of JME? In our opinion, the association is fortuitous: the presence of marked neurological and neuroanatomical changes did not significantly change the clinical and EEG presentation of JME, nor did it influence its pharmacological sensitivity, since the seizures were easily controlled by VPA.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence in a given patient of brain abnormalities and idiopathic generalized epilepsy, including JME, is possible. Such cases constitute exceptions (1/170 consecutive JME cases, i.e. 0.6% in our recent experience). There is probably no physiopathological link between JME, brain lesions and severe neurological impairment. Patients with a presumed genetic predisposition for JME are at equal risk for brain lesions as others subjects. They may still have a fairly typical form of JME, as long as the other electroclinical traits of the syndrome are present and differential diagnoses have been eliminated. In the very uncommon case reported here, JME had its usual benign course, and we found no diagnosis that better matched the clinical and EEG symptoms than the diagnosis of JME. It is hoped that less subjective diagnostic tools, e.g. those derived from molecular biology advances, will make the diagnosis of JME less debatable in the near future.