Epileptic Disorders

MENUGAD65-Ab encephalitis and subtle focal status epilepticus Volume 21, issue 5, October 2019

The syndrome defined as limbic encephalitis (LE) is evolving rapidly (Graus et al., 2016). Specific phenotype spectrums are progressively defined for each type of autoantibody (against cell surface membrane or intracellular antigen). Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) may be the main or the only initial feature in LE (Brenner et al., 2013; Gaspard, 2016; Serafini et al., 2016). LE associated with glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibodies (GAD65-Ab) remains understudied, whereas other GAD65-Ab disorders such as stiff person syndrome and cerebellar ataxia are better characterized (Honnorat et al., 2001; Saiz et al., 2008). The encephalitis phenotype associated with GAD65-Ab seems, in fact, to be a major neurological syndrome associated with GAD65-Ab. LE and non-LE may be both observed (Najjar et al., 2011). However, actual reports on encephalitic clinical pattern in patients with GAD65-Ab (epileptic disorders and associated features such as anxiety, mood disorder, and memory impairment) remain only general without accurate qualitative data (Najjar et al., 2011; Gagnon and Savard, 2016; Daif et al., 2018). The common effort of classification (based on clinical, paraclinical and prognostic features) is essential to optimize treatment and improve the functional outcome of these patients.

We report three consecutive cases of GAD65-Ab encephalitis patients followed in our neurological department for which we detail specific epilepsy features that seem to be particularly relevant to this disorder.

Case studies

Patient 1

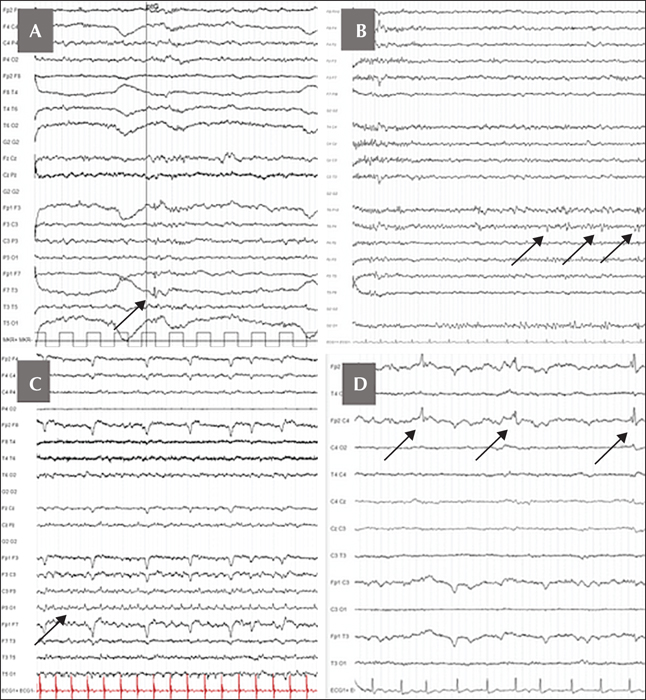

A 33-year-old woman, with no medical issue, was first admitted to the emergency room for a first generalized tonic-clonic seizure in September 2016. After a detailed interview, she reported a “dreamy state” feeling with abdominal pain over a year. These episodes could last several hours to days without a clear start and end. The initial standard EEG performed during the asymptomatic period showed only intermittent theta activity with few left anterior temporal sharp waves. She received specific treatment with levetiracetam but was also treated for a few months with escitalopram and praxepam due to severe and subacute anxio-depressive disorder. During the neurological follow-up, the “dreamy state” was still persistent under antiepileptic drugs and she started to complain about her memory. The long-term video-EEG monitoring revealed a strong argument for left mesial TLE, with abundant left anterior temporal spikes occurring specifically during sleep (figure 1A).

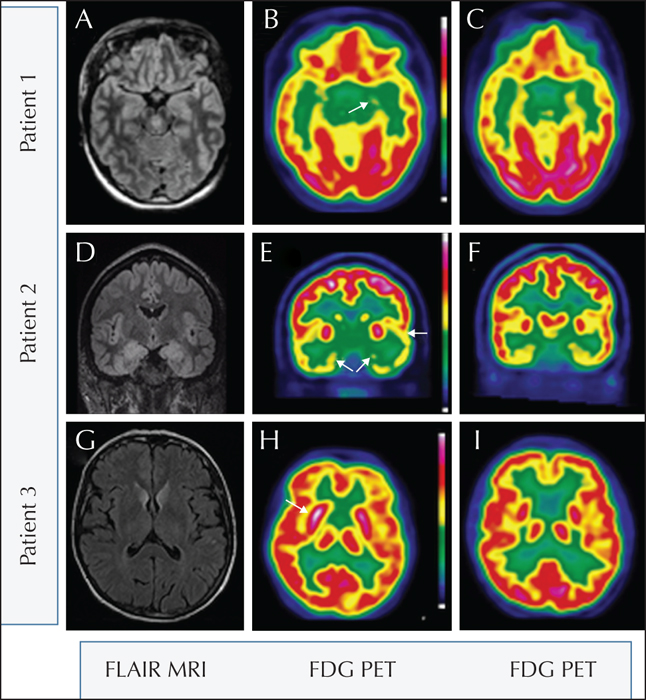

Initial investigation of this new-onset TLE was normal: MRI, laboratory workup, and a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study (normal cell count and protein, no oligoclonal bands). Brain 18F-FDG PET, performed four months after the clinical onset, revealed left temporo-mesial hypometabolism (figure 2B). GAD65-Ab was positive at a rate of 1,215 UEIA/mL (ELISA Isletest™-GAD ref 7009 BIOMERICA; normal <1,000 UEIA/mL) in the serum and higher than 250 IU/mL (ELISA Medipan; normal

She received four cycles of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), combined with antiepileptic drugs (levetiracetam then lamotrigine and benzodiazepine). Symptoms of anxiety and depression improved. Brief “déjà-vu/déja-vécu” still remained but only once a month and for a few seconds. Due to pregnancy, IVIG was interrupted. Immunosuppressive treatment (rituximab) was initiated just after pregnancy. Currently, the situation remains stable with monthly focal seizures. There was no cerebellar ataxia or cognitive complaint. Neuropsychological testing could not be performed because of French language difficulties (her maternal language was Arabic from Comoros).

Patient 2

A 30-year-old woman, without medical history event, presented in August 2015 with two successive generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The medical interview revealed possible temporo-mesial seizures over several weeks, characterized by an ascending gastric discomfort, a feeling of anxiety, palpitations, sometimes unpleasant smells, and a “déjà-vu/déjà-vécu” feeling. This feeling was frequent and could last several hours, described as a “strange dreamy state”. She also reported paroxysmal awakening with anxiety during night-time. A depressive mood with deep sadness, unprovoked crying, and dark thoughts started quite abruptly at the beginning of the epilepsy. Type 1 diabetes requiring insulin therapy was diagnosed a few months after the onset of seizures. She complained about her memory with altered autobiographic memory (she could not remember the day her daughter was born). The neuropsychological evaluation revealed dysexecutive disorders and working memory impairment. Standard episodic memory evaluation was normal.

The initial standard EEG showed right anterior temporal intermittent theta activity. However, on long-term video-EEG recording, we noticed few right temporal spikes only during sleep (figure 1B), arguing for a right temporo-mesial epilepsy. On cerebral MRI, bi-hippocampal T2/Flair hyperintensity was observed (figure 2D). The CSF analysis was normal (normal cell count, normal protein, and no oligoclonal bands). GAD65-Ab was positive in serum (1,239 UEIA/mL) and highly positive in CSF (DOT EUROIMMUN; normal <15). High IA2-Ab (4,000 IU/mL; ELISA EUROIMMUN; normal 18F-FDG PET, performed one year after the epilepsy onset, revealed diffuse bitemporal (internal and external) and left perisylvian hypometabolism (figure 2E).

Treatment with IVIG was initiated. Despite several trials of antiepileptic drugs (levetiracetam, lamotrigine, eslicarbazepine, carbamazepine, and benzodiazepine), her epilepsy became pharmacoresistant with weekly temporal seizures characterized by a brief “déjà-vu/déjà-vécu”. Mood disorders improved significantly with escitalopram. In parallel, control of type 1 diabetes improved and insulin could be reduced. Because of a desire for pregnancy, IVIG was pursued, avoiding immunosuppressive medication.

Patient 3

A 63-year-old woman was admitted in December 2015 for suspicion of stroke as an emergency secondary to three episodes of transient motor aphasia (lasting for less than one hour each). Several days before, she presented with five successive and transient stereotypic events, characterized by brief right ear tinnitus and motor aphasia, lasting 5-15 minutes. The initial standard EEG showed left lateral temporal status epilepticus (figure 1C). Levetiracetam was introduced.

She was readmitted two months later for a confusional state, followed by generalized tonic-clonic seizure. Her husband also described paroxysmal behavioural disturbances with major anxiety, agitation, aggression, and screaming. A long-term EEG recording showed, during sleep, intermittent delta activity in the left temporo-parietal lobe and right frontal spikes (figure 1D). Paroxysmal behavioural disturbances, characterized by agitation, opposition, and aggression, were probably related to frontal epileptic seizures.

The initial MRI was normal. Three months later, the control MRI showed T2/Flair hyperintensity of the caudate nuclei and right anterior cingulum (figure 2G), corresponding to hypermetabolism on brain 18F-FDG PET (figure 2H). CSF revealed 18/mm3 lymphocytes, CSF protein level was 0.53 g/L, with 11 oligoclonal bands. In the serum, GAD65-Ab was subnormal (1,049 UEIA/mL), but more than 250 IU/mL in the CSF (ELISA Medipan; normal

The neuropsychological assessment revealed cognitive difficulties with dysexecutive impairment and difficulty in lexical access. All clinical and paraclinical features argued for extra-LE.

She was treated with IVIG, cyclophosphamide, and then mycophenolate mofetil. Unusual anxiety with psychomotor acceleration still remains. She reports less than one seizure per month (mutism and loss of consciousness) under lamotrigine and eslicarbazepine. Control brain MRI showed atrophy evolution towards caudate nuclei, and brain 18F-FDG PET regression of the hypermetabolism (figure 2I).

For all patients, other onconeuronal and cell-surface protein autoantibodies were negative based on negative immunofluorescence performed on brain sections. Scan TAP and whole-body 18F-FDG PET revealed no neoplasia.

Discussion

GAD is an enzyme that allows the synthesis of GABA from glutamate, the main CNS inhibitory neurotransmitter. GAD65-Ab is commonly described in diabetes as well as three neurological disorders (Saiz et al., 2008): stiff man syndrome (Chang et al., 2013), encephalitis (Gagnon and Savard, 2016), and cerebellar ataxia (Honnorat et al., 2001). The encephalitis phenotype associated with GAD65-Ab seems to be characterized by frequent and severe TLE (Falip et al., 2012; Daif et al., 2018). In a recent study, almost all patients with GAD65-Ab encephalitis had initial seizures, and a quarter displayed status epilepticus. Epilepsy remained intractable in half of the cases (Gagnon and Savard, 2016). GAD65-Ab encephalitis phenotype appears to differ from that associated with other antibodies with less cognitive and psychiatric impairment (Malter et al., 2010; Daif et al., 2018).

We report three patients with confirmed GAD65-Ab encephalitis (positive antibodies in CSF). For all, the initial symptom was new-onset focal status epilepticus. Patient 1 and 2 reported an intense and prolonged dysmnesic experience (over several hours) without clear paroxysmal events. Neuropsychiatric comorbidities, a lack of initial standard EEG, and resistance to antiepileptic drugs made the interpretation of these subtle events complex. Prolonged EEG performed during the asymptomatic period provided an additional argument for an epileptic disorder, only during sleep. Retrospectively, the duration of these episodes (several hours) was clearly in favour of recurrent temporo-mesial status epilepticus. Semiology was more obvious for Patient 3, who started with recurrent prolonged atypical aphasic disorder. In this case, EEG during the symptomatic period showed direct evidence for lateral temporal status epilepticus. Neuropsychiatric comorbidities (mood disorders and mnesic or dysexecutive impairment) were frequent and possibility linked to status epilepticus.

The semiology described here appears to be different from that of other auto-immune encephalitis, such as LGi1, CASPR2, AMPAR, and GlyR, with a more insidious and subtle semiology. Epilepsy is a core symptom of GAD65-Ab encephalitis (Daif et al., 2018; Vinke et al., 2018). Additional epileptic symptoms (psychiatric and cognitive) exist, but may be misdiagnosed without careful interview. For two of our patients, epilepsy diagnosis was not obvious and long-term video-EEG was essential to correlate this exclusive subjective semiology to recurrent temporal lobe status epilepticus. In the literature, the description of seizures is limited, but intense subjective impairment (such as dysgueusia and dysosmia) has previously been reported in a review (Gagnon and Savard, 2016). The two first patients presented with LE semiology with temporo-mesial seizures, whereas the third patient clearly presented with lateral temporal and frontal seizures arguing for non-LE. Neocortical and deep grey structure hyperintensity on MRI was in agreement with this encephalitic pattern. Two similar cases have been reported in the recent literature (Najjar et al., 2011). GAD-Ab encephalitis appears to involve either limbic or extra-limbic structures, however, focal status epilepticus seems to reveal the pathology in all cases.

Taken together, our observations and the data from the literature suggest that GAD65-Ab should be screened in the CSF of patients with unexplained new-onset focal status epilepticus, especially when there is predominant subjective semiology. Careful anamnesis and paraclinical examination with a long-term EEG recording are essential to determine the diagnosis of epilepsy mediated by GAD65-Ab. In accordance with our three cases, pharmacoresistant epilepsy appears to be the main neurological problem in the clinical follow-up of GAD65-Ab encephalitis patients, even under optimized immunosuppressive treatment (Falip et al., 2012; Gagnon and Savard, 2016; Daif et al., 2018). Cognitive and psychiatric disorders, although less predominant, should be followed to better characterize the clinical outcome for this encephalitis.

Supplementary data

Summary didactic slides are available on the www.epilepticdisorders.com website.

Disclosures

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.