Epileptic Disorders

MENUExceptional response to brivaracetam in a patient with refractory idiopathic generalized epilepsy and absence seizures Volume 20, numéro 1, February 2018

Brivaracetam (BRV), a 4-n-propyl analogue of levetiracetam (LEV), is the most recently marketed antiepileptic drug (AED). This novel synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) ligand displays 10 to 30 times higher affinity to this integral transmembrane glycoprotein than its precursor. SV2A modulates synaptic vesicle exocytosis, ultimately leading to neurotransmitter release. However, the exact role of this protein in the pathogenesis of epilepsy is yet to be determined (Xu and Bajjalieh, 2001). BRV is currently indicated as adjunctive therapy for patients with focal-onset seizures with or without secondary generalization. However, evidence suggests that BRV may be an AED with broad-spectrum efficacy (Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenite et al., 2007; Matagne et al., 2008; Kwan et al., 2014; Steinig et al., 2017). We present the case of a patient with refractory idiopathic generalized epilepsy whose absence seizures improved considerably in terms of frequency and intensity after starting treatment with BRV.

Case study

Our patient was a 49-year-old woman with no relevant personal or family history, who reported onset of absence seizures at the age of 9 years. She was initially treated with ethosuximide (1,500 mg/day); treatment was discontinued after a seizure-free period of several years. At the age of 16, the patient experienced a first generalized tonic-clonic seizure and began receiving valproic acid (VPA) at an initial maintenance dose of 1,000 mg/day. Despite treatment, she experienced two further tonic-clonic seizures, the second of which occurred when she was 34 (the dose of VPA was gradually increased).

At the age of 42, the patient was referred to our department due to recurrence of absence seizures. These occurred during the days before menstruation (up to four or five seizures per day). During the episodes, she suddenly stopped all activity (seizures usually occurred while she was performing mental activities or holding a conversation), remained with eyes open and an empty gaze, and was unable to react to any stimuli; she displayed no other symptoms. Episodes finished abruptly, after which the patient resumed the activity she was doing. Brain MRI at that time revealed no abnormalities. An EEG performed while the patient was awake displayed frequent interictal spike-wave epileptiform discharges, which were medium-voltage, synchronic, bilateral, and symmetric, though slightly more predominant in both frontal regions, and clustering in trains at a frequency of 3 Hz, lasting for a mean of 1-2 seconds. In addition to her normal treatment (VPA dosed at 1,500 mg/day), she received lamotrigine dosed at up to 100 mg/day; treatment led to a significant reduction in the number of episodes. Several additional drugs, in polytherapy with the previous two, were attempted in order to ensure better control of seizures, but all had to be discontinued due to ineffectiveness (LEV at 1,500 mg/day, zonisamide at 500 mg/day, topiramate at 400 mg/day, and progesterone at 100 mg/8 hours during the second half of the menstrual cycle) or severe secondary effects (depressed mood and suicidal behaviour in the case of LEV, digestive complications and vomiting with ethosuximide at 1,000 mg/day, and dizziness and excessive daytime somnolence with clobazam at 30 mg/day).

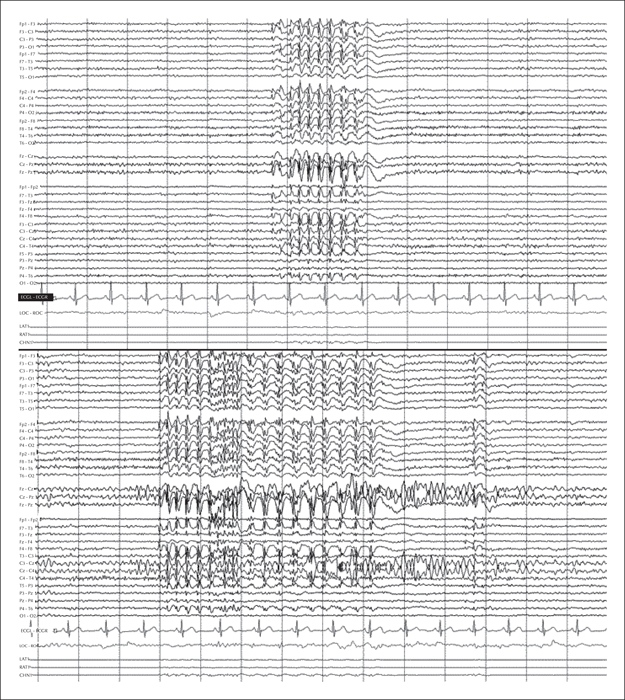

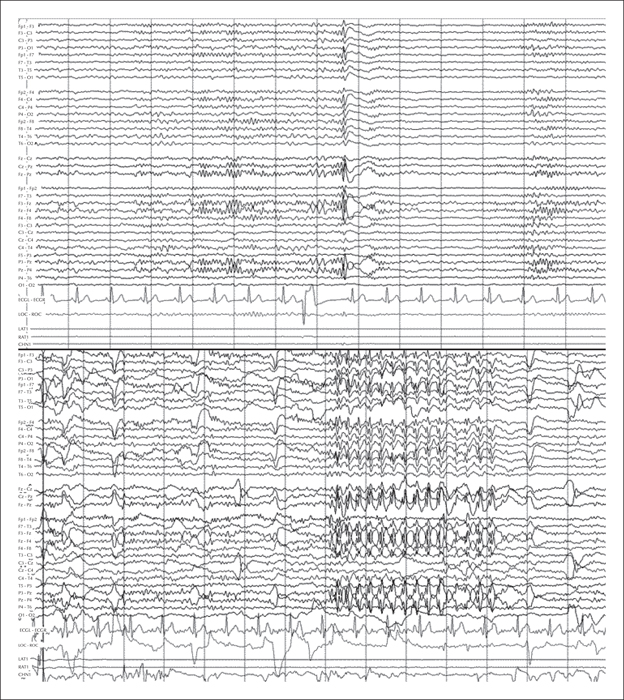

Seven years later, our patient experienced a severe, spontaneous exacerbation of seizures; 24-hour video-EEG monitoring recorded over 40 clinical events of absence seizures in addition to the electrical activity previously described (figure 1). Lamotrigine dose was initially increased to 150 mg per day, leading to a significant reduction in the number of episodes, however, this had to be reduced due to poor tolerance which manifested as frequent vomiting. Although BRV is not indicated for this type of epilepsy and our patient responded poorly to LEV, we decided to start treatment with this new AED dosed at 50 mg/day (the maintenance dose was subsequently increased to 100 mg/day). Our patient responded exceptionally well, remaining asymptomatic from the first week of treatment. An additional 24-hour video-EEG recording revealed only one short absence seizure and much shorter and less frequent interictal discharges (figure 2).

Discussion

Despite the wide range of AEDs available on the market, a significant percentage of patients fail to achieve satisfactory control of epileptic seizures, which results in substantial limitations in daily life activities and consequently a considerable decrease in these patients’ quality of life. This situation is especially frequent in patients with generalized epilepsy, for whom very few pharmacological treatment options are available and surgery is not considered. In the light of the above, new well-tolerated AEDs are needed that may be easily added to normal treatment for patients with uncontrolled or refractory seizures.

BRV is the latest AED on the market. It is currently indicated as an adjunctive therapy for focal-onset seizures with or without secondary generalization in epileptic patients older than 16 years. However, BRV has been suggested to provide broad-spectrum efficacy given its similarity to LEV and based on the results from preclinical studies on animals (Matagne et al., 2008) and other reports of patients with genetic generalized epilepsy (Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenite et al., 2007; Kwan et al., 2014; Steinig et al., 2017). Furthermore, some researchers suggest that this AED may be more effective for this type of epilepsy than for focal seizures (Kwan et al., 2014). In addition, BRV appears to be more effective as treatment for absence seizures(Matagne et al., 2008)than other generalized seizures, such as myoclonias (Kalviainen et al., 2016). In this context, and despite a poor response to LEV, we decided to administer BRV to our patient (her consent was required), achieving an excellent response. We hypothesized that the significant difference in response between the two drugs was due to the higher affinity of BRV for SV2A, although it should be noted that the compliance with LEV was probably irregular based on the adverse effects that it generated in the patient.

Based on our results and the favourable safety and tolerability profile of this AED, we recommend that treatment with BRV should be considered on a case-by-case basis in patients with refractory generalised epilepsy, while further data is generated from future studies on this topic.

Supplementary data.

Summary didactic slides are available on the www.epilepticdisorders.com website.

Disclosures

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.