Epileptic Disorders

MENUAntiepileptic drugs: evolution of our knowledge and changes in drug trials Volume 21, numéro 4, August 2019

Division of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology, Department of Internal Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Pavia, Pavia and IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy

- Mots-clés : epilepsy, therapy, antiepileptic drugs, clinical trials, history, review, ILAE 110th anniversary

- DOI : 10.1684/epd.2019.1083

- Page(s) : 319-29

- Année de parution : 2019

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

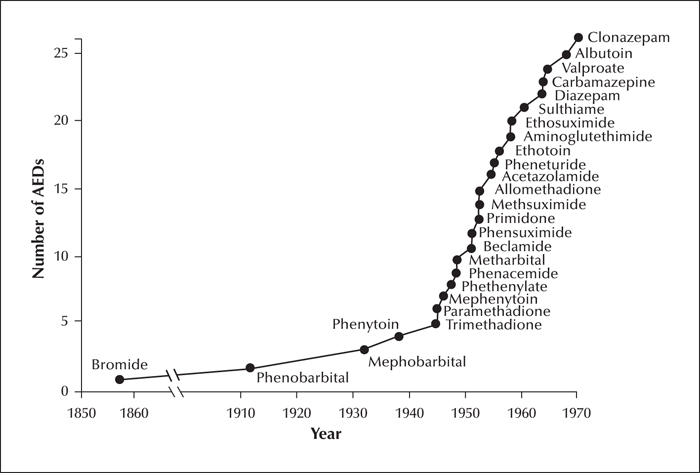

Clinical trials provide the evidence needed for rational use of medicines. The evolution of drug trials follows largely the evolution of regulatory requirements. This article summarizes methodological changes in antiepileptic drug trials and associated advances in knowledge starting from 1938, the year phenytoin was introduced and also the year when evidence of safety was made a requirement for the marketing of medicines in the United States. The first period (1938-1969) saw the introduction of over 20 new drugs for epilepsy, many of which did not withstand the test of time. Only few well controlled trials were completed in that period and trial designs were generally suboptimal due to methodological constraints. The intermediate period (1970-1988) did not see the introduction of any major new medication, but important therapeutic advances took place due to improved understanding of the properties of available drugs. The value of therapeutic drug monitoring and monotherapy were recognized during the intermediate period, which also saw major improvements in trial methodology. The last period (1989-2019) was dominated by the introduction of second-generation drugs, and further evolution in the design of monotherapy and adjunctive-therapy trials. The expansion of the pharmacological armamentarium has improved opportunities for tailoring drug treatment to the characteristics of the individual. However, there is still inadequate evidence from controlled trials to guide treatment selection for most epilepsy syndromes, particularly in children. Second-generation drugs had a very modest impact on drug resistance, and a change in paradigm for drug discovery and development is needed, focusing on treatments that target the causes and mechanisms of epilepsy rather than its symptoms. Testing potential disease modifying agents will require innovative trial designs and novel endpoints, and will hopefully lead to introduction of safer and more effective therapies.