Epileptic Disorders

MENUMusicogenic epilepsy with ictal asystole: a video-EEG case report Volume 23, numéro 4, August 2021

Musicogenic epilepsy is a rare form of complex reflex epilepsy with a prevalence of one in 10 million [1]. It classically presents as right temporal lobe onset seizures triggered by music. Likewise, ictal asystole is a rare cardiac consequence of epileptic seizures with a probably underestimated prevalence of 0.3 to 0.7%, mainly occurring during seizures of temporal lobe origin [2, 3].

Because of the scarcity of both musicogenic epilepsy and ictal asystole, to our knowledge, these two features have not previously been reported in the same patient. This patient with right temporal lobe epilepsy had both musicogenic seizures and ictal asystole, documented by video-EEG (V-EEG).

Case study

This 30-year-old female was admitted because of intractable seizures which begun at the age of 17. She had no family history of epilepsy. Seizures lasted between 40 and 120 seconds and were characterized by an unpleasant feeling followed by speech arrest, sweating, tachycardia, facial flushing, then pallor. Despite levetiracetam at 2,000 mg/day and carbamazepine at 800 mg/day, she suffered from four to six seizures a month. Brain MRI was unremarkable. Although her epilepsy was potentially eligible for surgery, the patient refused stereo-EEG procedures. In November of 2017, the number and severity of seizures increased. The seizures occurred in clusters of six to 11 seizures a month. Clinical presentation evolved with falls occurring in about half of the seizures, 20 to 40 seconds after their onset. These falls were occasionally traumatic, although the aura frequently allowed the patient to lie down before losing consciousness. As the patient was in charge of her new-born, she apprehended the falls and their consequences. This aggravation led to repeat V-EEG.

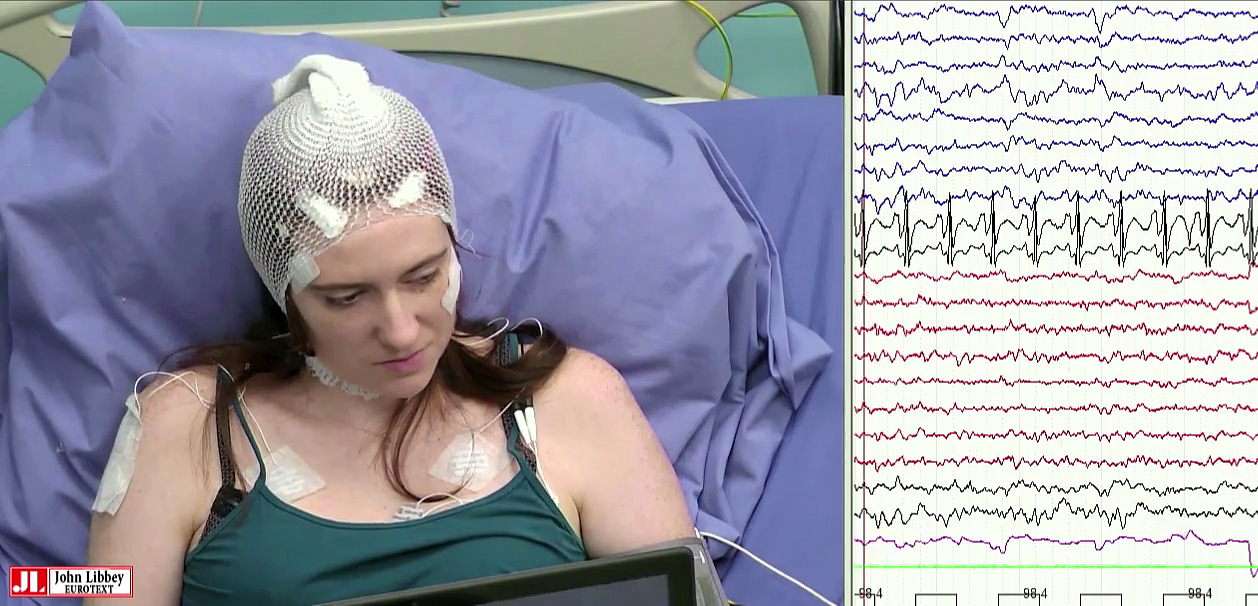

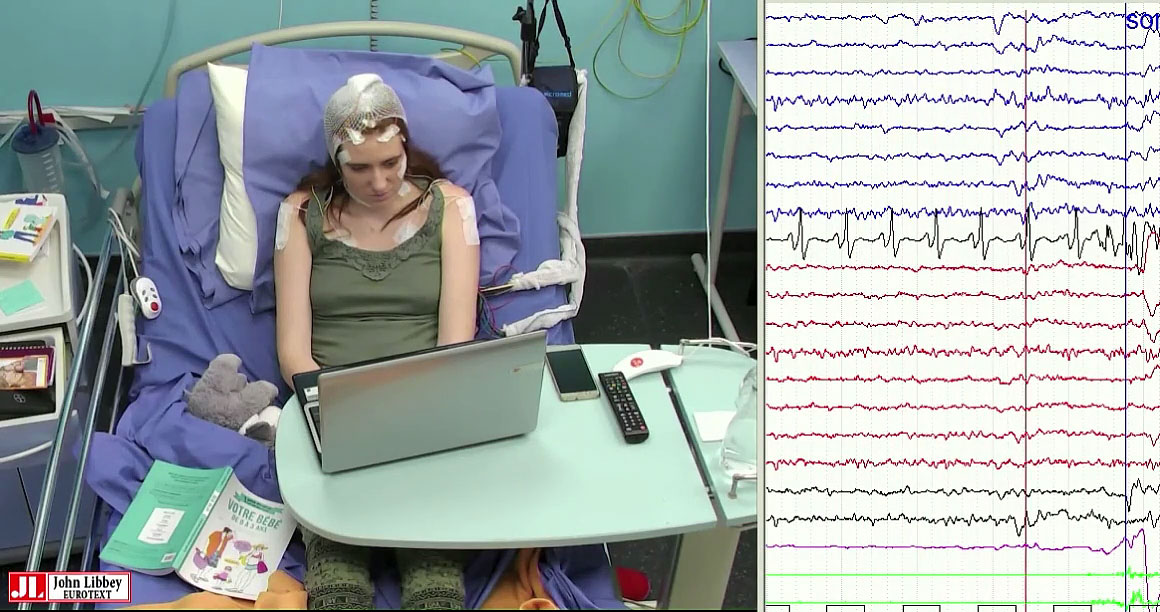

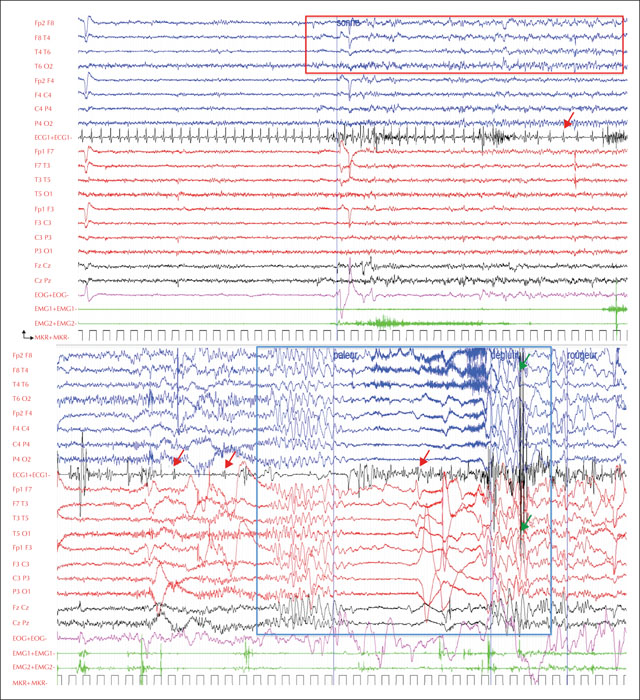

At admission, the patient reported that certain music samples could induce her seizures. Four seizures were recorded within five to 10 minutes after hearing and watching a music clip on YouTube that was particularly effective in inducing the seizures, entitled “Olé” by D. J. Assad (figure 1, video sequence 1); a French electro-hip-hop artist [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JqurEoNhNj4]. The patient was able to warn that a seizure was imminent due to a subjective unpleasant feeling that built up 10 to 20 seconds before the episode started. She would then stare and show impaired responsiveness, followed by hypotonia, pallor and loss of consciousness 30 to 45 seconds after the warning. Subtle clonic movements of both upper limbs occurred 10 seconds later and the patient would then return to full consciousness with almost immediate return to normal colour. The EEG showed isolated right temporal spikes as the patient warned of the seizure, followed by rhythmic theta activity over the right temporal area appearing as the patient stared. The EKG then revealed 10 to 15-second bradycardia while the patient lost consciousness. Cardiac asystole then occurred 30 to 45 seconds after the ictal onset and lasted for five to eight seconds. Two seconds after the last QRS complex before the asystole, sudden generalized slow delta waves appeared on the EEG, followed by voltage flattening, a few jerks on the electromyogram, and again generalized slow delta waves before normalization of the EEG and state of the patient. No spontaneous seizures were recorded, although the patient reported that these were similar to provoked seizures. Several tests were then performed whilst the patient was:

- •watching the video clip without the music;

- •listening to the repetitive rhythmic patterns of the music repeatedly;

- •listening to other songs by the same singer;

- •and listening to the music without watching the associated video.

The patient's usual seizures were only induced by listening to the music, without watching the associated video (video sequence 2). Brain FDG-PET was normal. The diagnosis of right temporal lobe musicogenic epilepsy (ME) with ictal asystole (IA) was made based on these elements.

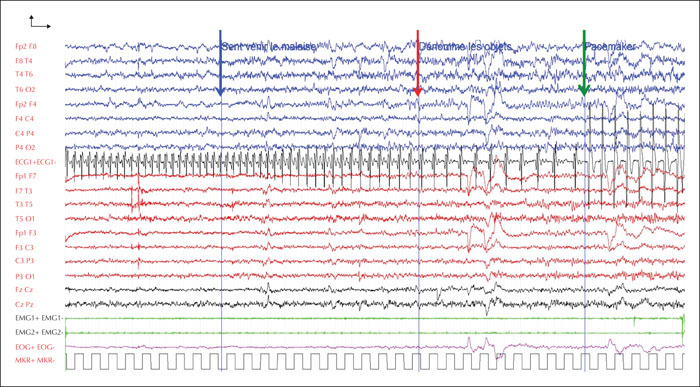

After a multi-disciplinary discussion, a mono-chamber pacemaker (St. Jude Medical) was proposed to the patient, and was implanted. The decision was supported by the patient's refusal of surgery, the presence of repeated falls and spontaneous seizures, and their potentially traumatic consequences. Follow-up V-EEG showed considerable improvement in ictal semiology, thanks to the pacemaker activation, that prevented the syncopal component of the seizures. Two provoked seizures were recorded during a short 24-hour video-EEG, with no spontaneous seizures. Clinical features were identical for all seizures; the patient stared and then demonstrated a slower verbal and motor response without any falls that lasted 90 to 100 seconds. Electrophysiological anomalies were restricted to a rhythmic theta activity over the right temporal area, similar to the activity at the onset of seizures recorded before pacemaker implantation (figure 2). In the patient's everyday life, since implantation of the pacemaker, the frequency of seizures has reached four to six a month and there has been no complete loss of consciousness or any fall.

Discussion

Reflex epileptic seizures are epileptic events that are always elicited by a specific stimulus. The encountered stimuli vary from elementary sensory triggers such as light flashes, sound and hot water to complex activities such as reading, calculating or listening to music. Reflex epilepsies have not been included as a specific syndrome in the latest ILAE classification and should instead be identified by their seizure type and etiology [4]. ME is a rare form of complex reflex epilepsy. Although musical stimuli may be highly variable, stimuli may also be very specific for a given patient. Triggers range from listening to a particular portion of a specific song, to hearing or playing any piece on a particular instrument or by a specific composer. These triggers correlate to the different components of a musical stimulus, which can all individually induce seizures: rhythm, harmony, melody, emotional impact and memory [5]. In parallel, intracerebral EEG studies have revealed inconsistent seizure foci, involving most often right and rarely left temporal lateral or mesial structures [6]. Heschl's gyrus has been identified as the seizure onset zone in only one case [7]. Tayah et al. [8] have therefore suggested that different syndromes coexist within ME, based on the seizure-provoking component, which reflects the ictal onset zone. In our patient, only listening to the song as a whole would trigger the seizures after a latency of five to 10 minutes. These findings are consistent with most reports that identify the degree of emotional impact as the main trigger rather than the auditory content of the music [6, 9], and could suggest a limbic rather than a neocortical seizure onset. The existence of spontaneous seizures prior to the emergence of the musical trigger supports the hypothesis that the involved limbic connections remodel over time, facilitating provoked seizures [6].

Ictal cardiac arrhythmias have often been reported, generally presenting as tachycardia in temporal lobe seizures, with a prevalence of 80 to 100% [10]. In patients undergoing long-term V-EEG monitoring, IA can be observed, mostly in left temporal lobe seizures, with a much lower prevalence of 0.3 to 0.7% [2, 3, 11]. These should be suspected when atonic loss of consciousness or tardive falls occur in the course of a typical seizure. The pathophysiology of IA is still unclear today, but many authors [3, 10, 12] have suggested the involvement of central neurovegetative centres including the insular cortex, the anterior cingulate gyrus and the amygdala in the epileptic discharge. Insular lobe stimulation in humans and animal models has confirmed its ability to induce IA, and although some have suggested left-sided epileptogenesis, consistent lateralization has never been confirmed [13, 14]. The scalp-EEG study of our patient's seizures only showed right temporal seizure activity at the onset of the ictal asystole. The propagation of the seizure to the ipsilateral insular region would be in line with current knowledge. Contralateral involvement of the insula through transcallosal connections cannot, however, be ruled out without stereo-EEG investigation. The high frequency of IA in our patient made us concerned about the possible consequences, such as seizure-related injury and sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP). However, although ictal cardiac arrhythmia is supposedly relevant to the pathogenesis of SUDEP, all the identified cases in the largest retrospective study were secondary to generalized tonic-clonic seizures, leading to a postictal neurovegetative breakdown and post-ictal cardiac arrhythmias [15]. On the contrary, prolonged cerebral hypoperfusion in the case of IA causes the ictal discharge to break down and the IA then terminates, thus explaining its self-limiting course [6]. The decision to implant the pacemaker was agreed upon with our patient, after optimizing AEDs and discussing surgery which she refused. The principal purpose was not to prevent SUDEP, but rather prevent falls and their consequences.

Conclusion

The association between musicogenic seizures and IA in our patient might be coincidental. However, the insular lobe's connections with both the limbic regions and the autonomic nervous system could explain the emotionally-charged musical trigger as well as the cardiac consequences of our patient's seizures, respectively. This case highlights the need for precise electroclinical assessment of seizures that change clinically over time, in order to better predict the onset zone, suggest ultimate surgical treatment, and prevent complications associated with seizures.

Supplementary material

Summary slides accompanying the manuscript are available at www.epilepticdisorders.com.

Acknowledgements and disclosures.

The authors thank Dr. Fabien Squara for his collaboration and expertise concerning the cardiac management of the patient.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.